The Art-o-Maat

Vending Machine Miniature Artwork

Marie Arleth Skov

Punk Art: An Exploration

October 2018

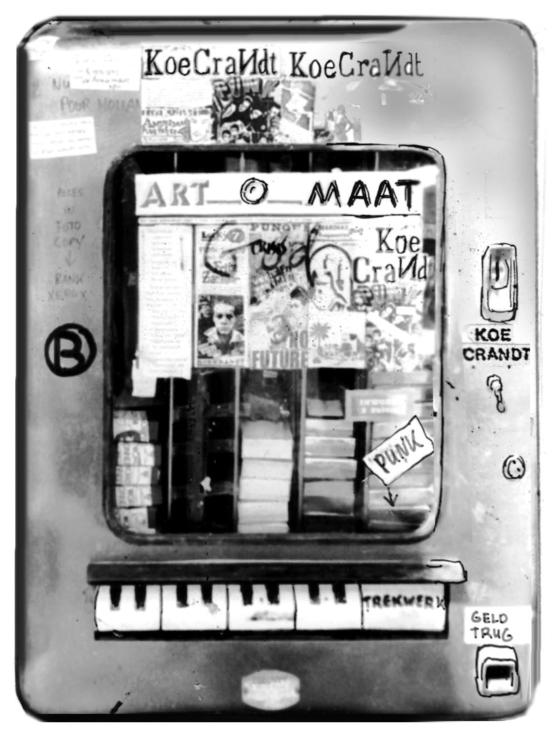

One of the most noted art actions by the KoeCrandt group was their series of so-called Art-o-Maats (1977-1978.

The Art-o-Maats were converted cigarette vending machines, with their original content removed and replaced by small

boxes containing miniature artworks, tiny zines and poem collections, or other small items fitting into the size of a

cigarette pack, such as small-sized smoke bombs (smoke cakes). With an almost Pop Art-like use of punk symbols, the

artists decorated the devices with nails, scissors, safety pins, and razor blades, but they were still recognizable as

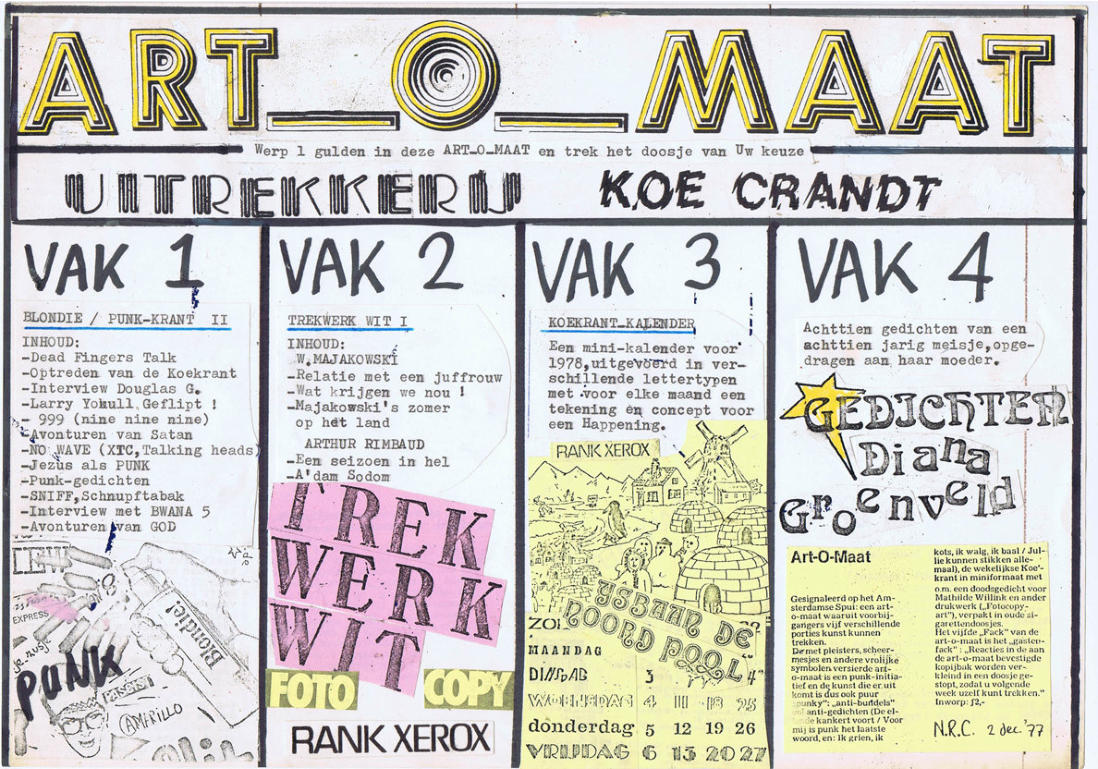

former cigarette vending machines. By inserting two guilders, it was possible to choose between five different options,

matching the five cigarette brands

before. Beneath the output compartment, the artists put an idea box for the buyers. In the first Art-o-Maats, the

KoeCrandt group still used old cigarette packs, which they asked for or bought, but the packs of cigarettes were

expensive compared to the rolled tobacco they usually smoked, and they began making multiple boxes out of cardboard

using a template.

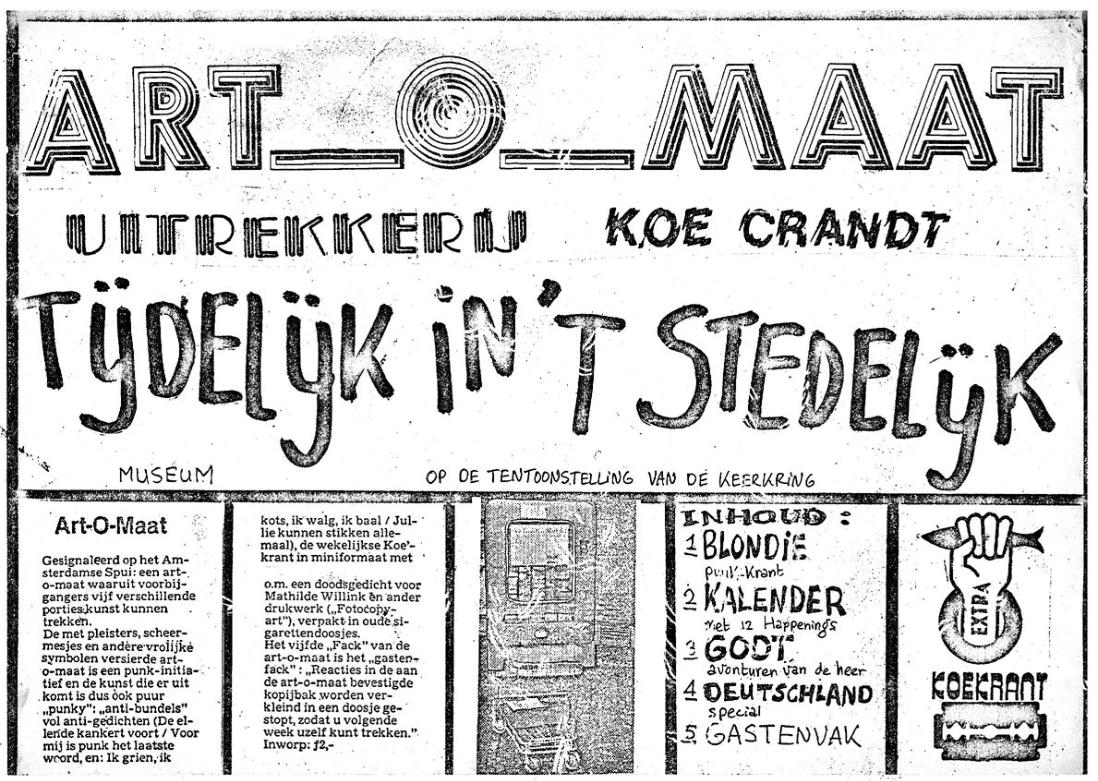

The Art-o-Maats were placed all over Amsterdam, and sometimes moved around. One device was in the theater De

Brakke Grond, one in Café Scheltema, one was in the bookshop Athenaeum, one in a supermarket. The chosen sites

were thus a mixture of high and low. Ironically, one Art-o-Maat was placed on the Spui, where the illustrious anti-

tobacco-company happenings of Robert Jasper Grootveld had taken place in the 1960s. According to the artists, the one

that sold the most was placed in the Stedelijk Museum. "The guards in the Stedelijk Museum were shocked that people

were putting in money, so they were buying art in the museum. Doing something economical in the museum, perhaps

even without the museum knowing? How disrespectful! Of course, we liked that." The equation of art and commodity

was one of the points of the action. The artists played with the appropriation of commercial selling tactics and with the

lowbrow connotations of merchandise, not unlike what the Buzzcocks were doing at the same time in the UK with their

PRODUCT imprint.

"The shops complained about the smoke bombs, because people would open them inside the shop," Kaagman recounts,

but overall, the response to the Art-o-Maats was positive, "Xerox even sponsored us! Because of the Art-o-Maats.

We thought that was cool." The sponsorship from Xerox shows both how the public perception of punk had not yet

consolidated and how open the punk scene still was—a sponsorship was just a practical means, there was nothing to sell

out. "[With the sponsorship from

Xerox] it became possible to make huge amounts of photocopies. Xerox machines were still very rare. Hugo and Kristian

went there and talked to them, said they were artists," Ozon says, "Back then, it was so early, punk was still interesting,

fashionable.

The Xerox people had no idea. Punk was not yet connotated with squatting, graffiti. The magazines were writing:

'This is the new fashion, it is the new music, it is from London, it is from New York, Andy Warhol likes it!' So, the Xerox

people did not know what punk really was, what we were doing. They did not know that it was really something coming

from underneath, from kids."

The Art-o-Maats combined several elements of punk art. With the Art-o-Maats, art was literally at street level.

The art vending machines thus symbolized both cheap and accessible culture. The artists engaged with notions of the

automatic and the Pop Art subject of the copy, rather than original, of art as a serial machine production.

There was a playful element in this art-to-go, and perhaps also an element of the childish.

The sensation of placing a coin in a machine is associated with colorful candy

machines and the calculated small surprise of bulk vending. This childish ambience is further enhanced through the

miniature formats. The Duchampian notions both of chance and of the miniature, which we also saw in the doll record

player used by The Deadly Doris for Choirs and Solos, are thus present in the Art-o-Maats. Duchamp's semi-private

engagement with the course of his own work likewise finds an echo. "I photocopied all of my work, also my private

work, from when I was a girl, and put it into little boxes in the vending machine," Ozon recounted.

The collaborative concept of the Art-o-Maats is, furthermore, similar to that of George Maciunas' Flux-Kits (the first one

was made in 1962), which variously contained works by Joe Jones, Mieko Shiomi, Alison Knowles, George Brecht, and

others, as well as miniature editions of Fluxus newspapers, fitted into a converted attaché case.534 In Europe, the Flux-

Kits were distributed through the Amsterdam-based European MailOrder Warehouse/Fluxshop of Willem de Ridder,

incidentally also the founder of Paradiso. Both in the Art-o-Maats and the Flux-Kits, poetry and interaction were key

actors. The Flux-Kits contained performance score cards and artworks to be touched and handled, for example a

noisemaker by Joe Jones, which thus had an effect comparable to the small smoke bombs in the Art-o-Maats. The main

difference, however, was that the Art-o-Maat was placed on the street. Indirectly, the punk criticism of Fluxus as an art

form for the privileged few art collectors is thus repeated

in the format of the Art-o-Maat in comparison with the Flux-Kits. The Fluxus attaché cases were advertised at 100 US

dollars—not a high price, we might argue—but nonetheless, more expensive than the punk artworks in the Art-o-Maat

(2 guilders). More important however, was the means of dissemination: the Art-o-Maat concept emphasized street art

notions of intervention in the flow of everyday life, the involvement of the passerby, and general accessibility; in

opposition to the friendsof-friends trade of the Fluxus editions.

Marie Arleth Skov October 2018