Punk & Post-Punk Volume 9 Number 3

MARIE ARLETH SKOV

Kunstbibliothek (Art Library), Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

The 1979 American Punk Art dispute: Visions

of punk art between sensationalism, street art

and social practice

ABSTRACT

In May 1979, a conflict arose in Amsterdam: the makers of the exhibition

American Punk Art clashed with local artists, who disagreed with how the curators

portrayed the punk movement in their promotion of the show. The conflict

lays open many of the inherent (self-) contradictory aspects of punk art. It was

not merely the ubiquitous ‘hard school vs. art school’ punk dispute, but that the

Amsterdam punk group responsible for the letter and the Americans preparing the

exhibition had different visions of what punk art was or should be in respect to

content and agency. Drawing on interviews with the protagonists themselves and

research in their private archives, this article compares those visions, considering

topics like institutionalism vs. street art, avantgarde history vs. tabloid

contemporality and political vs. apolitical stances. The article shows how the

involved protagonists from New York and Amsterdam drew on different art

historical backgrounds, each rooted in the 1960s: Pop Art, especially Andy

Warhol, played a significant role in New York, whereas the signature poetic-social

art of CoBrA and the anarchistic activity of the Provos were influential in

Amsterdam. The analysis reflects how punk manifested differently in different

cultural spheres, but it also points to a common ground, which might be easier to

see from today’s distance of more than forty years.

INTRODUCTION

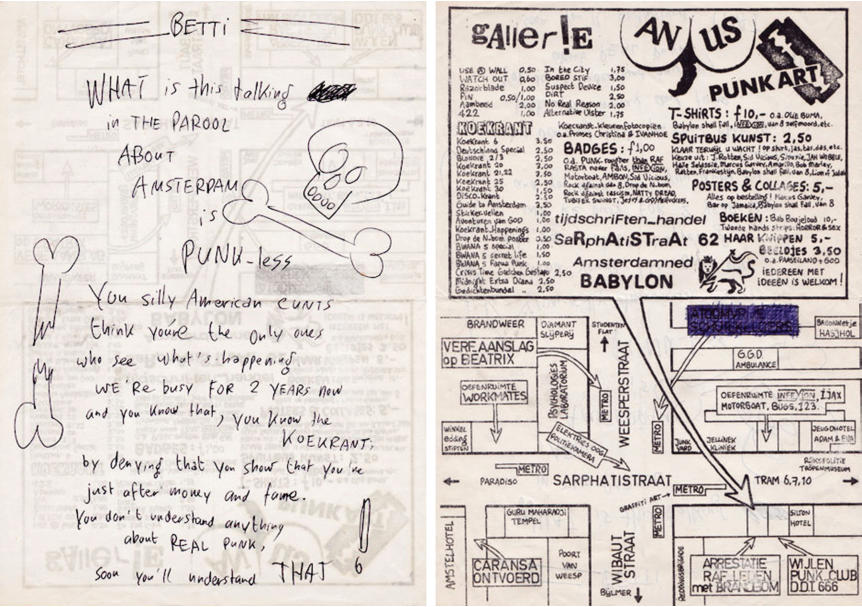

Amsterdam, end of May 1979. On the door of the exhibition space, Art

Something hangs a handwritten message, signed with a skull and bones:

You silly American CUNTS think you’re the only ones who see what’s

happening […]. You don’t understand anything about REAL PUNK,

soon you’ll understand THAT!

The letter was written on the backside of a flyer for their own punk art gallery,

subtly called ANUS (Figures 1a and 1b). The reason for the angry letter was

the upcoming show American Punk Art, showing works by around twenty

New York artists. Local punk artists had taken offence to the way the punk

movement was described and promoted by the makers of the exhibition. The

curators of American Punk Art, which indeed did show in Amsterdam from 1

to 23 June 1979, were Marc Miller and Bettie Ringma, who had also been the

initiators behind the first Punk Art exhibition at the Washington Project for the

Arts in Washington, D.C., in 1978. After the extensive media attention received

by that punk art show, Miller and Ringma did two reiterations: a one-night

event at the School of Visual Arts in New York, and subsequently travelled to

the Netherlands to set up the American Punk Art exhibition at Art Something.

In the following, we will first turn to that initial show in the United

States, and look at the agenda of the initiators, before then turning to punk in

Amsterdam. To understand how the dispute arose, and why that angry letter

was pinned to Art Something’s door, cultural background is key; after all, punk

manifested differently, yet still consistently, in different cultural spheres. ‘It was

image, not sound, that defined the early days of Dutch punk’, writes historian

Jerry Goossens (2011: 202). As much as that might have been true in many

countries – that punk was visual as much as it was musical – it was perhaps

especially obvious in the Netherlands. Furthermore, punk in the Netherlands

drew on a twentieth-century countercultural history of social art, squatting

and graffiti, most prominently impersonated through the 1960s anarchistic

protest movement, the Provos. The punk artists in focus in this article, who

were centred around the Sarphatistraat in Amsterdam, identified with that

tradition, as we shall see.

The reaction of the punk community in Amsterdam, when faced with the

American Punk Art exhibition, demonstrates the complexity and sometimes

paradoxicality of punk (and thus, also of the expression of punk in art). Punk

was style, surface, publicity stunts and ironic affirmation of teenage mass

culture. Punk was also underground social practice, riots, resistance and radical,

poetic philosophy. Perhaps what bound these different versions of punk

together was an ideal of self-determination – but we will return to that question

in the end…

NEW YORK PUNKS: ‘JUST LOOKING FOR ACTION’

The image used on the invitation and the poster for the Punk Art Exhibition

was a work by Bettie Ringma and Marc Miller themselves, in collaboration

with Curt Hoppe: Smashed Mona (1978). It showed a black and white

reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa (ca. 1503–06) behind smashed

glass,

with the title PUNK ART spray-painted across the image, above and beneath

Mona Lisa’s face (Figure 2a). It was a fairly simple gesture of destruction,

outbreak and Marcel Duchamp reference. The image seemed to suggest that,

whereas Duchamp in L.H.O.O.Q. (1919), had only bestowed the Mona Lisa

with a moustache and suggested her ass were on fire (L.H.O.O.Q. = Elle a

chaud au cul), punk art would simultaneously break her free of the museum

glass and more irreversibly and recklessly demolish the Old Masters. It was an

easy provocation, and as a recognizable key visual for the exhibition, it worked

well. Smashed Mona went on the cover of the exhibition catalogue, too, while

the reverse by Scott B. and Beth B. (Figure 2b), with the punning title Max Karl

(1978), showed the image of a naked man lying on the floor kissing the shiny

black funnel-heel slip-ons of a woman standing over him.

The impetus for the Punk Art Exhibition came from the fact that the New

York punk scene was full of visual artists. Miller – who was at the time an art

history student at NYU and personally involved in both the art and the punk

scenes – explains: ‘[w]e didn’t have a very big roaster [sic] there, so it filled

up pretty quickly’ (Miller 2018: n.pag.). The ‘not very big roaster’, to which

he refers, was The Washington Project for the Arts, an art space led by Alice

Denney. Denney had been an important advocate of Pop Art in the 1960s, and

when Miller and Ringma approached her with the idea of a punk art exhibition,

she saw punk art as a similar faction. In an interview with Howard Smith,

she recounted:]

A lot of people are upset. Many of the board members obviously don’t

even consider it a valid art form. But I knew better than to be put off by

pejorative responses. I did the first Pop Art show down here back in ‘66,

long before that was considered acceptable.

(Denney quoted in Smith 1978.)

At 50, the press dubbed her the ‘Doyenne of Punk’, a role she gladly embraced.

Denney also had the connections to set up an interview for the catalogue

of the Punk Art Exhibition: Billy Klüver interviewing Andy Warhol and Victor

Hugo. Klüver remarks: ‘I was sitting in Max’s [Kansas City] the other day and

someone told me that you are the hero of the punks, Andy. Everyone is reading

your books’. The three of them discuss a punk girl who cut her wrists at

Hugo’s party. Hugo: ‘[b]ut that is too bad because she cannot sell that. She has

impressed people but she doesn’t get any money for it. Just a little publicity.

Fame and no money’. Warhol: ‘And a few cuts’ (Hugo et al. 1978: n.pag.). The

short exchange shows the mutual fascination of the late Pop Art scene and

punk, but also a certain incomprehension; perhaps fame, no money and a few

cuts were all the punks wanted, at least at the outset.

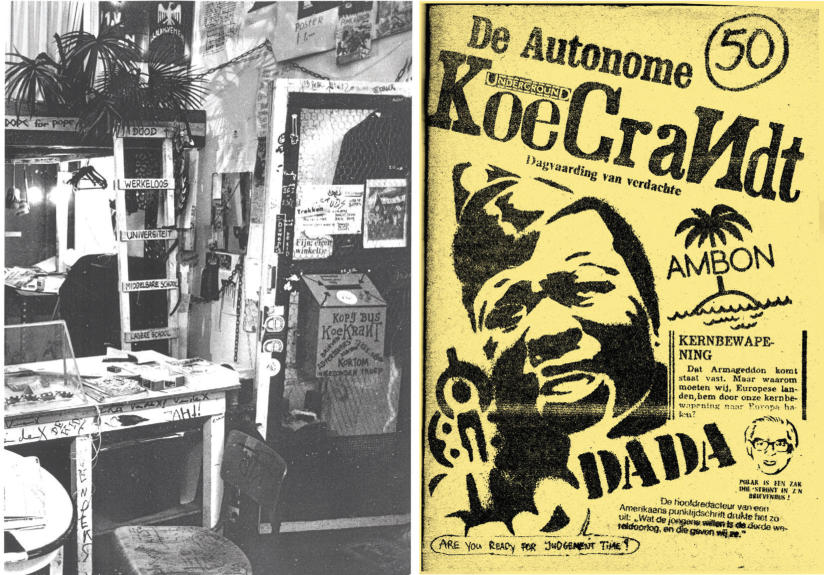

Kaagman argues:

In Amsterdam, we had a tradition of graffiti, first and foremost the Provo

movement. They wrote their name all around Amsterdam. So, there was

already a tradition of murals and graffiti.

With punk, Amsterdam became the graffiti capital of Europe, Jonker (2012:

155) argues in NO Future NU. Dr Rat aka Ivar Vičs incorporated both punk

and graffiti and played a significant role in the development of the scene

(Haas 2011). Vičs’ pseudonym – Dr Rat –combined several elements: the ironic

‘Doctor’, the reversed letter combination r-a-t-/a-r-t, which Nina Hagen sang

about in ‘Dr. Art’,1 and of course the rat, a punk symbol par excellence. The

punks adopted the rat as a mascot, with whom they shared the city as their

biotope. At the same time, the rat is an important symbol in street art, as can

be seen for examples in 1970s stencils by Blek le Rat and in Christy Rupp’s The

Rat Patrol (1979).

Graffiti, and specifically the link between punk and graffiti, connects the

two cities, New York and Amsterdam. East Village street artist Kenny Scharf

notes:

Street art in general was punk […]. The act of doing street art was punk.

You were risking getting thrown in jail. I actually was thrown in jail.

(Kenny Scharf, quoted in Lewisohn 2008: 76)

The late 1970s and early 1980s street art works in New York drew on the edgi

ness of illegality. Cedar Lewisohn bluntly summarizes:

The best street art and graffiti are illegal. This is because the illegal works

have political and ethical connotations that are lost in sanctioned works.

(Lewisohn 2008: 127)

Aside from this illegal assertion, there is another – not unconnected – feature

that graffiti and punk share: a sense of barbarism, tribalism, archaism. The

Surrealists, for example, saw street art as primitive and childlike, and attributed

an anti-civilized insistence to it. In 1933, in a feature about ‘the bastard

art of the streets’ in the surrealist magazine Minotaure, Surrealist photographer

Brassaï wrote about street art: ‘[i]ts authority is absolute, overturning all the

laboriously established canons of aesthetics’. (Brassaï in Minotaure, quoted in

Lewisohn 2008: 29). Because graffiti and street drawings are immediate, they

evoke a sense of honesty.

There were other shared features between punk and graffiti in the late

1970s, such as their involvement with decline, dirtiness, ephemerality and

indeed their social criticism, for example, in works like John Fekner’s Decay

or Broken Promises (New York, 1980, Figure 8). Punk and graffiti shared a

no-nonsense approach that is also conveyed in the rapidness of their activity:

Graffiti had to be executed as quickly as possible to avoid getting caught, and

speed was a quintessential punk approach. Both sprayed and stenciled graffiti

are, furthermore, associated with military and paramilitary messaging, in

part due to the covertly famous ‘Kilroy was here’ inscriptions. The clandestine

comrade and guerilla notions of graffiti, likewise fit with punk’s self-image

as resistance. The goal of establishing an alternative way of communicating,

outside the mainstream, is thus also present both in the punk zine culture and

in graffiti. Kaagman explains:

In order to get new people, [we would] write our names and slogans on

the street, so they would know punk is still alive.

(Kaagman 2017: n.pag.)

With this link between graffiti and punk, we return to the Americans in

Amsterdam. After all, graffiti would have been one key connecting element

between the punk art scenes in New York and Amsterdam, as it is quite

pronounced in those two cities particularly. However, Marc Miller and Bettie

Ringma chose to focus on other aspects, especially in their public promotion

of the exhibition.

AMERICANS IN AMSTERDAM:

‘EGO-TRIPPING AND ATTENTION GRABBING’

The reason Marc Miller and Bettie Ringma had the idea to go to Amsterdam

was that Ringma was Dutch and knew Karen Kvernenes, who owned Art

Something. After the shows in Washington and New York, punk art had

momentum. The exhibition had to be reduced to avoid shipping costs, but

it still featured most of the key names from the US show. The flyer accompanying

the exhibition announced a series of events at the Kunsthistorisch

Centrum, including a panel discussion with Ringma and Miller with the title

‘punk art: sex, geweld, geld, en sensatie’ (‘Punk art: Sex, violence, money,

and sensation’) on 8 June 1979. In a large article on the front page of the

art section Parool Kunst of Het Parool, under the headline ‘Punk Art: schreeuw

om andacht’ (‘Punk art screams for attention’), Miller and Ringma were

interviewed, and Ringma stated:

The emphasis in all this art, and also the music, which we call punk, lies

on violence, sensation, ego-tripping, and attention-grabbing.

As in Washington and New York, the element of hype was again emphasized

in this third iteration of the show. Furthermore, the two curators dismissed the

local scene in the interview:

We did not know anything. We did not know there were any punks

in Amsterdam. We knew there were punks in England, we had met

the Damned. But there were punks in Amsterdam, it turned out, and

some of our quotes in Het Parool did not go down well with them, we

said like ‘there is no punk in Amsterdam’ which was just ignorance,

so they got rattled up. But ok, in the show in Washington, we had a

punk band playing against a disco band, you know, you want a battle,

you want a fight, you want a little tension. This time it was not deliberately, but,

you know, it got us a lot of write-ups, and nothing bad

happened. The punks put a note on our door, and we got some negative

reviews.

Miller accounts. He also explains the addition of American to the Punk Art title

of the show:

Around that time, it was becoming increasingly clearer that a lot was

happening in London, and it was different. So that was why we tagged

on American to Punk Art in the title, which annoyed a lot of people! I

think, maybe they could’ve given us a pass.

(Miller 2018: n.pag.)

No such thing would happen. Ozon explains her anger:

We thought it was posh American art which had nothing to do with

punk. And indeed, it had nothing to do with the kids here in the streets.

But they were saying ‘this is how it is’ […] it was such an arrogance.

(Ozon 2017: n.pag.)

Kaagman adds:

Sure, we wrote that ‘anonymous’ note. We were non-commercial, both

the musicians and the artists. […] And why did they not come to us?

They never came to us, we had to go them! Who the fuck do they think

they are? We were not jealous, but we thought they were stealing our

movement!

(Kaagman 2017: n.pag.)

Thus, the problem lay in the representation of punk, in the attention it got

in the local media, and also in the lack of interest for punk in Amsterdam.

Kaagman:

Typical American. They think they know better. And they know nothing

about what is going on here, about squatting, or anything. […] We went

to the opening but we never talked to them. They had no roots here,

they did not check out what was going on here.

(Kaagman 2017: n.pag.)

It was not only the punks who were complaining about the show. The reaction in

the established Museum Journal gives a hint of the incomprehension with which

punk art was met. Feminist art historian Rosa Lindenburg

complained that the works were ‘macho art’, and among others criticized

Robert Mapplethorpe as an ‘anti-feministic’ artist, who ‘glorifies the male

body’, which – in the context of Mapplethorpe’s progressive, liberal stance

and his fight for LGBT rights – seems almost like parody of a stereotypically

bigoted feminist position. Lindenburg’s lack of comprehension did not interest

either side within the punk art conflict.

Another review, however, hit the curators harder. On a note of self-reflection,

Miller admits:

The review that stung the most was by Gerard Pas in Artzien. […] He

was our first friend in Amsterdam but his negative review caused a

temporary estrangement. It contained more than an ounce of truth and

it still resonates (and hurts) today.

(Miller 2019: n.pag.)

Under the title, ‘The great art swindle???’, Pas writes:

This brings us to the reason for this criticism and that is the ‘American

Punk Art’ exhibition. I believe that the premises of such an exhibition

are quite justified although I find that the way in which this collection

of material has been compiled under the title ‘American Blah Blah’ is

truly facinorous and that they who have been involved in expressing

the product of their labor over the last years would be saddened by the

lapidicolous manner in which their works have been handled by the

organizers whose names fill the pages of Het Parool.

(Pas 1979: n.pag.)

Pas asserted that it was not the artists in the exhibition, but rather the makers of

the show, who were ‘ego-tripping and attention-grabbing’, as Ringma had put

it. The integrity of the artists, Pas argued, was compromised by the superficial

branding of their work. If we go back to the original exhibition in Washington,

an Associated Press reporter quoted one ‘Helen, an art gallery owner who uses

no last name’ and who had a ‘crayon tattoo’ (not a real one) in demonstrating

the kind of horror Pas envisions: ‘Punk Art […] may be misunderstood, but it

should not be ignored’, the woman stated: ‘[i]n ten years everyone will want

to own some punk art’ (Miller 1978). If ever there were a hope in punk’s ‘No

Future’ it would be the avoidance of ending up as one more ‘at first

misunderstood, but now acclaimed’ eccentric art label, as celebrated and sold by

Helen,

SOME COMMON GROUND

Forty years later, the dust has settled. ‘We were total outsiders when we did

that show. Later I learnt more about the context’, Miller recognizes, whereas

Kaagman now concedes ‘[w]ell, perhaps the art itself was not that bad. Some

of it I actually really liked, it was pretty sick’. Two years after the American

Punk Art exhibition, the KoeCrandt artists showed their own punk art at the

same venue as the Americans, Art Something (Jonker 2012: 203). Despite the

remaining differences, there were connections in content and form, and, after

all, a few personal connections, too: ‘I knew Dr. Rat, because I knew Gerard

Pas, who was traversing the scenes’, says Miller. Ozon later had a dispute with

the same Rosa Lindenburg who had written the negative review about the

American Punk Art exhibition. She exclaims:

We were not condoning violence by showing it, we were just mirroring

it! It was ridiculous that it should be understood any other way!

(Ozon 2017: n.pag.)

Despite the inner conflicts between punk artists, they were closer to each

other than to their common enemy.

Miller actually points to two elements that bound the KoeCrandt artists

and himself: DIY and graffiti.

Half of it was do-it-yourself. Everybody was opening their own club,

everybody was starting a band, everyone was making their own publications.

We were storming the gates.

(Miller 2018: n.pag.)

Kaagman says:

I studied Dada, collage techniques, but I never went to art school. The

street was my school. Nobody was teaching what I wanted to learn:

stencils, felt pen. The art schools did not take that seriously, those were

junk materials. I thought they were wrong. And on the streets, I met

interesting people. […] But still, it was: Don’t follow a leader, lead yourself. Don’t

listen to the teacher, teach yourself. Do It Yourself.

(Kaagman 2017: n.pag.)

To a great extent, that DIY impetus was the same in different cultural spheres.

Furthermore, graffiti was a very important part of punk art in New York and

Amsterdam, more so than in other cities. Miller recounts that he and Ringma

at first wanted to bring in graffiti:

One decision, that we made with the original show, was not to include

graffiti, which we talked about. Today, I would’ve done that differently.

(Miller 2018: n.pag.)

Miller, however, was quite right, when he stated (above) that ‘a lot was

happening in London, and it was different’, as the reason why the exhibition

in Amsterdam was called American Punk Art. After punk’s explosion in the

United Kingdom, both with its connotations of working-class anger and with

its links to the ex-situationists in the radical (anti-)art/activist group King

Mob, the movement had indeed changed. At the end of the 1970s, that change

was about to intensify. In October 1978, Crass recorded their track ‘Punk is

Dead’ with the lines:

I see the velvet zippies in their bondage gear / The social elite with

safety-pins in their ear / I watch and understand that it don’t mean a

thing / The scorpions might attack, but the systems stole the sting.

(Crass 1978: n.pag.)

The calls for street action and for punks to engage with social issues just grew

stronger. Into the punk art show dispute thus played elements of apolitical vs.

political stances, and even within those political stances: capitalism vs.

socialism/communism (after all, it was still the time of the Cold War). ‘There is no

rock ‘n’ roll in Russia, there is no artistic freedom, there is no McDonald’s’, as

Legs McNeil had written in his Punk Manifesto (see Figure 5). McNeil wanted

pure bliss, speed and hedonism – no leftist lectures – in his punk.

Punk was a movement with many different strategies. One was the affirmation of

trash culture, the adulation of fast food, teenage sex, beer cans,

cheap dollars, cartoon excitement, tabloid hype. Andy Warhol’s provocations

loomed in this affirmation. It is an important point that this strategy was not

without critical edge: it was about overthrowing the bloated self-righteousness of

high culture and, especially within the art scene, about punctuating the bubble of

l’art pour l’art. Regardless of its relevance, such a stance

might however be misunderstood as hollow. Another punk strategy was the

one of the KoeCrandt artists, in which the social aspect was pronounced.

Interestingly, both strategies were closely linked to movements of the 1960s:

one a hardcore, splatter version of Pop Art, the other a doom version of

Situationist International. What they did have in common was a quest for free

space. In the end, the virulence of punk was heightened by these diverse

strategies; because it was a self-contradictory and mutating movement, punk did

mean freedom – artistic freedom and personal freedom.